Conventional wisdom suggests that living at high altitudes (above 2,500 m) is a significant challenge for sustained human habitation. In Africa, Ethiopia is home to 80% of the continent’s highest elevations, with alpine vegetation belts scattered across its diverse landscape mosaic. Lowland natives face many challenges in the Afroalpine, such as low temperatures, heavy rainfall, strong trade winds, high UV radiation, lack of plant food and hypoxia. The latter severely affects all facets of human life, including reproduction and labor. It is not surprising, therefore, that Ethiopia’s high altitudes have been widely perceived as a barrier and that prehistoric human settlement has mainly been attributed to external forces such as climatic or demographic pressures.

Recent archaeological research, however, has challenged these assumptions. Human presence in the Ethiopian highlands does not only date back hundreds of thousands of years. Multiple episodes of upland occupation with active use of the Afroalpine zone have occurred intermittently over the last 50,000 years. Surprisingly, the largest alpine ecosystem (Bale Mts.) witnessed a stable long-term hunter-gatherer settlement system under maximum glaciation conditions. However, seemingly favorable conditions prevailed in the lowlands. Conversely, humans did not retreat into the same ecosystem during hyper-arid lowland conditions. It is thus difficult to reconcile the discontinuous nature of human settlements at high altitudes directly with climatic and environmental changes. Novel approaches emphasizing the human factor are needed to explain the integration of high altitudes into the land-use systems of mobile prehistoric societies.

We hypothesize that dynamic shifts in population connectivity are a far better explanation of current patterns in the archaeological record. The ability to create and maintain wide-ranging social networks is a critical variable that allowed prehistoric people to exploit various adjacent ecozones in Ethiopia. These networks sometimes have extended beyond the boundaries of single ecozones. They led to the integration of high altitudes, whose cultural record always mirrored, among other things, regional signals. However, research needs to pay more attention to this regional scale instead of directly extrapolating results of the most minor scale (=sites) to large-scale, overarching issues. Disentangling the different scales of analysis is crucial and will help to find measures of population connectivity over time, a need that our research aims to address.

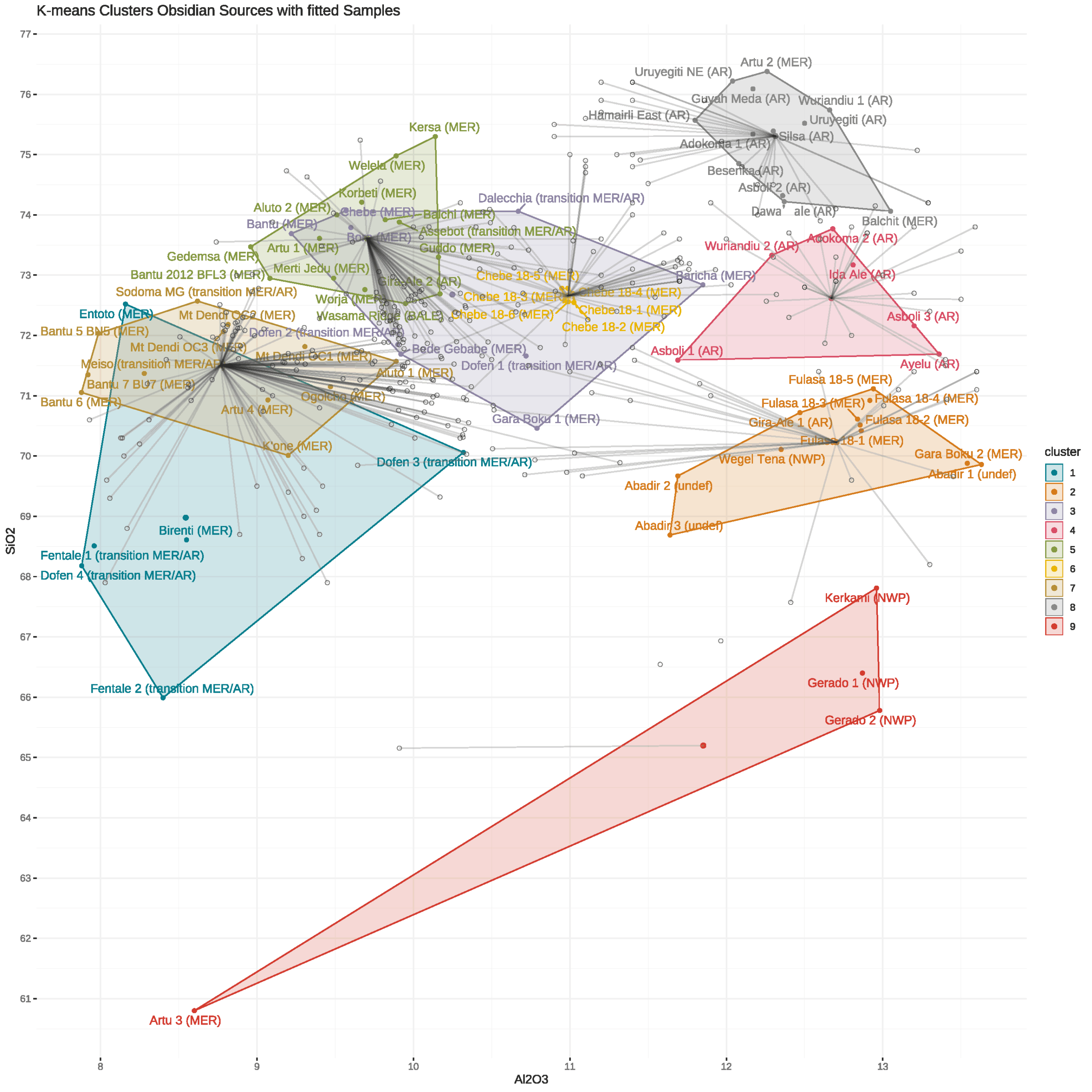

The newly established HESCOR project provides the ideal multidisciplinary environment to collect, link and analyze the necessary cultural and environmental data and to develop the means to measure prehistoric connectivity. We use geo-referenced and dated assemblage data as the basic units and will assess their respective ecological contexts. We then calculate and model the cultural connectivity inherent in different archaeological datasets (obsidian geochemistry, lithic technology, proxies for occupation intensity and mobility). This will enable us to demonstrate the existence, extent, transcendence, and dynamics of social networks in the past, thereby reshaping our understanding of prehistoric societies and their interaction with high-altitude environments.

Fig.1: View from the Afroalpine Plateau into the lowlands (Bale Mountains, SE Ethiopia).

Fig. 2: Reconstruction of population networks via movement of obsidian from geological sources to archaeological sites.