Learning has long been considered a key mechanism of human culture. Indeed, certain forms of learning, and the subsequent transmission of the knowledge so acquired, have been positioned as qualities that fundamentally set humans apart from other living organisms. But recent research in a range of fields – including ethology, the animal cognitive sciences, and multispecies studies – has demonstrated that nonhuman animals, too, are avid learners. Much of the plasticity (the ability of an organism to change its makeup and behavior) and historicity (not just the situatedness in time itself but the capacity for past experiences, perceptions, and memories to shape future outcomes) of living organisms – both of which are now widely regarded as defining features of life as such – may be a consequence of their ability to learn and thus adapt to changing conditions. Looking at the long-term evolution of the Earth system, learning therefore encapsulates some of the key dynamics of an ever-changing biosphere and should feature centrally in how we think about and examine the evolution of the Earth as a whole.

Joining forces, HESCOR working packages 2 and 9 seek to do precisely this – to deepen our understanding of the role of learning in the evolution of life in the Earth system. We are particularly interested in the question of how past humans – themselves part of the biosphere – learnt to live in changing environments, and how such learning was facilitated by interactions and relations not only among themselves but also with nonhuman organisms, especially animals with whom they shared those environments. We propose that this perspective on “environmental learning” offers a productive framework for rethinking human-environment interaction and for unravelling how different historically situated humans have made themselves at home in different ways in different places. Such learning is not only an important link between human agency and the potentials, possibilities, and pressures associated with particular environments and climates; it is likely also one of the overlooked drivers of the evolution of coupled human-environment systems.

But learning is not interesting for this reason alone. Human life is always “more-than-human” – it crucially relies on and benefits from a variety of nonhuman life. No life can be lived in seclusion; life is always lived relationally, within webs of life and livelihood, with different organisms shaping each other’s conditions of behavior, history and evolution. Learning plays an important role in this multispecies fabric of life, in which not only humans but varying constellations and configurations of other living beings participate.

This is where we enter novel terrain. In the past, learning has typically been understood as happening exclusively among conspecifics: humans learn from other humans, typically those close to them, such as members of the same social group. Chimpanzees, similarly, learn from chimpanzees, elephants from elephants, and older individuals often play a central role as repositories of knowledge to draw from. In this traditional understanding, however, learning remains confined within the narrow boundaries of “species islands,” never to escape. An Earth system perspective that takes recent multispecies insights seriously, we argue, cannot ignore the fact life is lived – and can only be adequately understood – beyond such species boundaries. In a changing biosphere imbued with plasticity and historicity, learning entails not only learning from conspecifics but also from our nonhuman co-dwellers. Such multispecies learning, arguably a highly consequential (deep) historical phenomenon generative of bona fide multispecies communities of life, has been largely overlooked, scarcely theorized, and rarely examined empirically. Addressing this oversight and its broader implications is one of the things we aim to achieve in HESCOR.

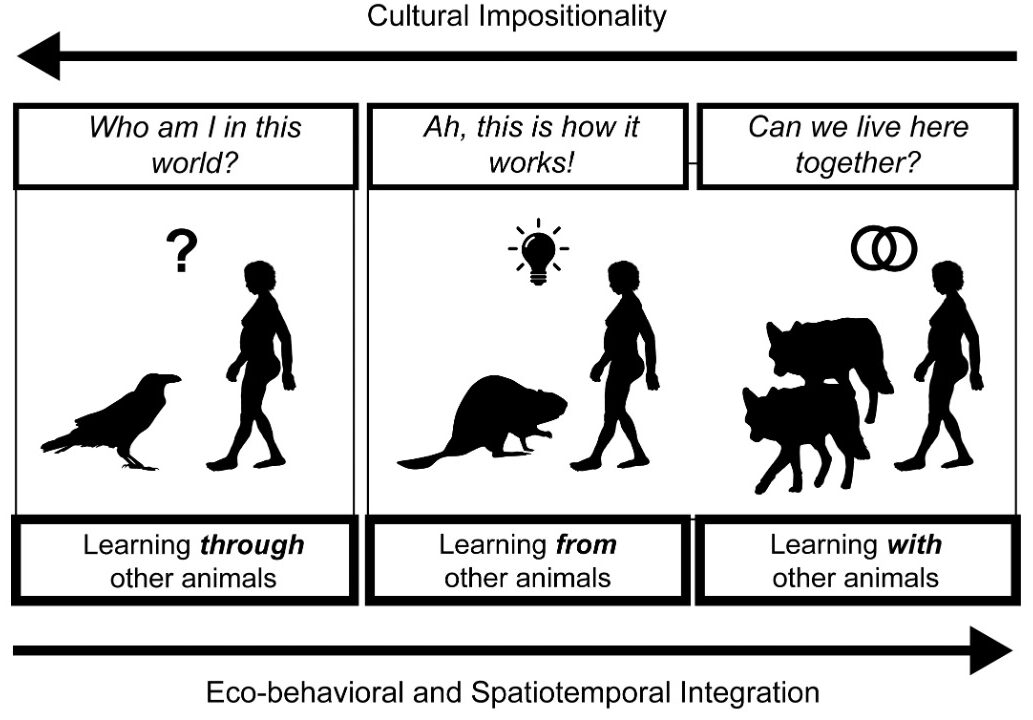

In order to facilitate this sort of investigation and to begin working out a theoretical framework for better understanding how learning interlaces with the evolution of behavior within such broader communities of life, we have begun to devise a threefold heuristic for different ways of learning environments with and from nonhuman animals. You can read the details of this new analytical framework in our newly available preprint, which also explores some preliminary applications of these ideas – as a proof of concept – by re-examining select historical and archaeological cases in light of this learning perspective to illustrate its largely untapped potential.

Schematic representation of the suggested threefold heuristic of animal-oriented modes of environmental learning.

This research has also inspired us to think more broadly about how humans operate in the Earth system, and how we can make better sense of key developments in early human history. The ZOOGESTURES project, which has recently received funding from the VolkswagenFoundation (2026-2029), is one of the fruits of these efforts. In ZOOGESTURES, an interdisciplinary team of researchers comprising multispecies archaeologists, philosophers of technology, and cognitive primatologists will for the first time examine whether key technological innovations and developments in early human evolution were influenced and shaped by behavioral and gestural repertoires of prominent nonhuman animals whom humans observed and learnt with.